Apr 26, 2023

Gaming the System: Modularity as the Key to Scalable Community Agriculture

Editor’s Note: The prestigious Wageningen University & Research recently hosted the Grand Finals of their third Urban Greenhouse Challenge with the goal of encouraging participants to develop an urban farming site “that significantly improves the quality of life of local residents in one of the most diverse lower-income neighborhoods of Washington D.C.” Following the conclusion of this Challenge, Agritecture sat down with members of the winning team, LettUs Design, namely Sarah Hoogenboom, Prathamesh Patalay, Eren Gozde Anil, and Mustafa Agbaria.

Food apartheids are making it increasingly apparent that a history of racialized segregation continues to divide our societies and threaten livelihoods.

Access to fresh produce, grocery stores, and affordable healthy food options is limited and made to be inconvenient only for specific communities. According to the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), “the racial demographics of the areas described by this term are most often Black and Latino. When comparing communities with similar poverty rates, Black and Latino neighborhoods tend to have fewer supermarkets that offer a variety of produce and healthy foods.”

Rather than taking a top-down design approach that fails to account for community needs and cultural knowledge, agricultural leaders argue that “focusing on creating food sovereignty through community-driven solutions and systemic change” is the path forward.

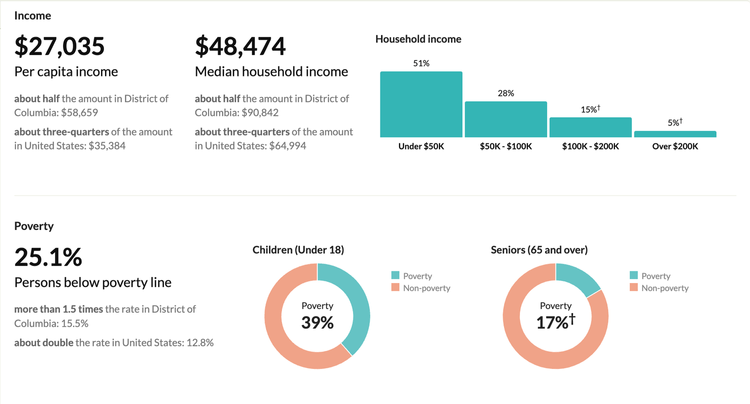

Ward 7’s income and poverty statistics. Data and charts sourced from Census Reporter.

This is precisely the challenge Wageningen University & Research (WUR) laid out for participants of the third Urban Greenhouse Challenge. Students were asked to design a “comprehensive plan to develop [the] East Capitol Urban Farm in Washington, D.C. into a site that enables robust and resilient year-round sustainable food production.”

Located in Ward 7, the site was traditionally a self-sufficient neighborhood. Today, it has the lowest number of grocery stores in the District. Additionally, disparity in access to healthy and affordable food has taken a toll on the health and well-being of residents as well as on the economy of the ward. These persistent problems plague the daily lives of residents.

Meet the Challenge winners: LettUs Design.

Winners of the third Urban Greenhouse Challenge, LettUs Design. Image sourced from Wageningen University & Research.

The interdisciplinary team consists of ten Master’s students from the Delft University of Technology (TU Delft) - 5 architects, 1 strategic designer, 2 water management experts, 1 environmental engineer, and 1 electrical engineer - coming together from 9 countries.

What’s interesting is that only a few of the team members came from an urban agricultural background, or with knowledge of plant science. Team Lead Manager and Designer, Sarah Hoogenboom, adds that “coming from a technical university posed an additional challenge for our team due to the Challenge being more social impact focused. We definitely had to up the ante, understanding the societal impacts of design.”

Strategic designer Prathamesh Patalay highlights that what makes this project interesting is that Ward 7 “isn’t the only location with these kinds of challenges. While this is an unfortunate reality, other locations, too, suffer from similar challenges. The benefit here is that they can easily replicate and benefit from these solutions.”

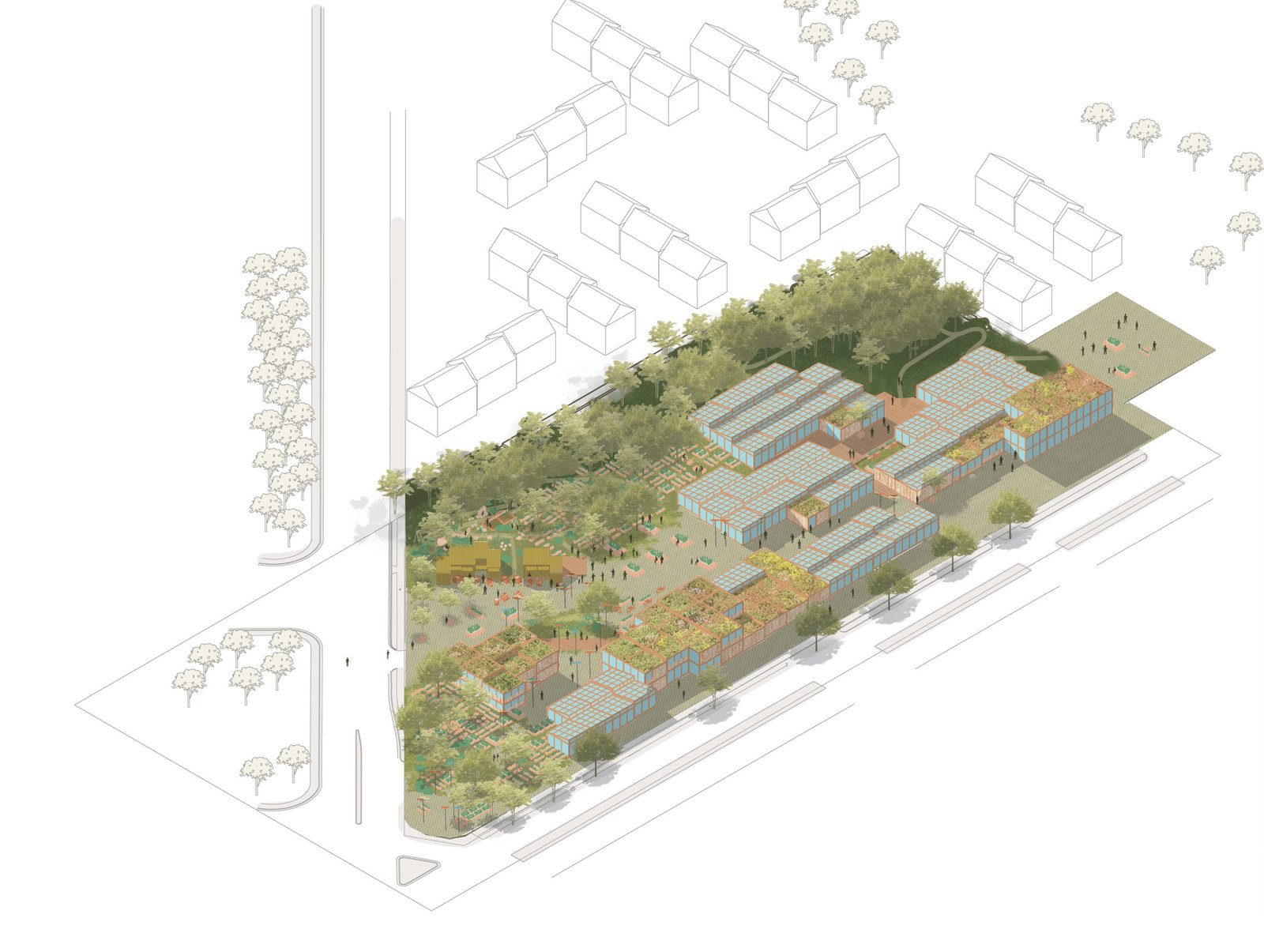

In their attempt to address the challenges of Ward 7, and create a replicable model for other locations, the LettUs Design Team proposes a modular urban agriculture concept that can be adapted to the needs of each community.

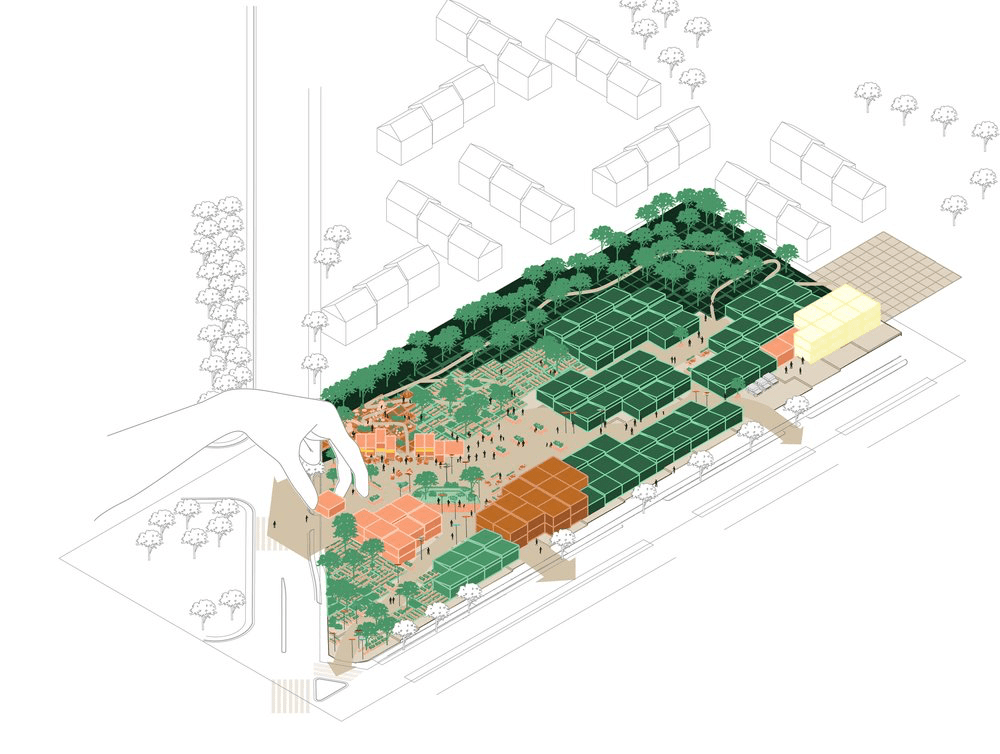

LettUs Design’s chosen modules for the gamification process with communities. Graphic sourced from LettUs Design.

With gamification at its core, aspects like food production, food processing, community involvement, social life and leisure, education, and employment are broken down into 6x6 meter modules. With a game board and site map that’s divided into a grid, modules are categorized as color-coded blocks, and brought to the community to figure out module placements.

Here, we can clearly see how the project “gives community members or leaders a chance to design for themselves, while we [the LettUs Design team] supply the tools to support decision-making,” shares architect Eren Gozde Anil. The goal here is to allow for local participation not only during the conceptualization of the concept, but also during the development and adaptation to possible future scenarios. “There is no one-size fits all solution, so we let them play and we let them decide.”

Rather than design for a community, gamification is allowing LettUs Design to design with the community.

Rendering of the proposed bioswale. Graphic sourced from LettUs Design.

Rendering of the outdoor workshop space. Graphic sourced from LettUs Design.

Rendering of the entrance area. Graphic sourced from LettUs Design.

Rendering of the community kitchen. Graphic sourced from LettUs Design.

Entrepreneur and electrical engineer Mustafa Agbaria highlights the helpful context that “coming from different backgrounds ourselves, as a team, we realized fairly early that we can never fully understand the challenges this community faces. But, the combination of our experiences helped us figure a path to move forward.” It's the interdisciplinary and diverse nature of the team that sparked the gamification and modularity ideas.

Hoogenboom adds how “a lot of times, there's a bit of disconnect between the people that designers are serving and the people that they think they're serving. With this gamification, which is becoming an increasingly popular way of city planning, we’re both empowering and educating the communities on how to take charge of their space.”

The modularity also applies to the agricultural pieces of the operation, which include hydroponic vertical farms, dutch buckets, aquaponic systems, vertical mushroom production, indoor and outdoor community gardens with raised beds, and more.

Visual representation of the gamification process on the game board. Rendering sourced from LettUs Design.

Anil adds that “we’ve designed the systems such that they can add up. For instance, we’re using NFT channels on A-frames, and those can be easily scaled up or down depending on the community needs or budget of the project. Similarly, with the dutch buckets, we can add more or less to the design.” Agbaria adds that “because of this, you can act based on what the community wants, what the community needs, and what resources are available to the community.”

The biggest benefit to this modular approach is scalability.

With his strategic design expertise, Patalay highlights that the project “can be phased up slowly, giving us the benefit of being able to start small.” As functions are introduced at different community phases based on financial viability, “we won’t need a lot of initial investment to get the farm started. Being able to start small also makes the project easier to execute for the community who is actually going to run it, and gives them more control over how the farm expands over time.”

The business model additionally intends to employ community members through strategies including a year-round subscription service, remote stalls, and partnering with local organizations for distribution. The team concludes that alongside government funds, the community will be able to finance the first few modules with such initiatives.

In realizing that “education is one of the best ways to empower people,” the team incorporated educational elements into all aspects of the project, shares Patalay.

Anil adds that the team’s “goal from the beginning was to create a space for everyone in the community, regardless of their age or occupation.” As a result, elements like the community garden, square, playground, and market facilitate spaces for connection. And, while the food production infrastructure offers hands-on farm and nutritional education, the team went above and beyond to ensure additional opportunities for learning.

Rendering of the community garden. Graphic sourced from LettUs Design.

Rendering of the outdoor weekend market. Graphic sourced from LettUs Design.

Beyond urban agriculture, Hoogenboom adds that an inclusively accessible interactive education path highlights the farming and sustainability practices on site. “This includes our rewilding, reforestation, and permaculture efforts - with these, we acknowledge that agriculture isn’t confined to farms, it also occurs naturally. So, this education path not only gives people access to natural spaces in urban environments, it also allows people to see different contexts in which food can be grown.”

Furthermore, to expand their educational offerings, “the site includes an extended campus for the University of the District of Columbia, offering certified courses focused on employment upskilling and training, helping the community find better work in the same domain,” according to Anil.

To top it off, circularity on-site was prioritized to limit waste and make the best of the resources the community had available. Anil highlights that “primary waste flows were reused by the food production chain - for instance, sawdust from maker spaces is used by the mushroom farm, while food and agricultural waste from the various farms and nearby school feed a vermicompost system.” Additional measures like rainwater harvesting and solar energy generation ensure increased self-sufficiency of the site.