Mar 11, 2019

Iowa's First 'Agrihood' Aims To Integrate Agriculture Into The Community

CONTENT SOURCED FROM DES MOINES REGISTER

Steve Bruere asks if he should dress like a farmer or a developer when he meets up with a photographer.

The 38-year-old is joking. He rarely strays far from an unremarkable suit and cowboy boots that take him from farmland auctions to corporate offices. But the question is appropriate: Bruere and his partners want to build what amounts to a small town on about 400 acres near Cumming, with an organic vegetable farm, vineyard, orchard and residential gardens anchoring the massive home, condo, apartment and retail development.

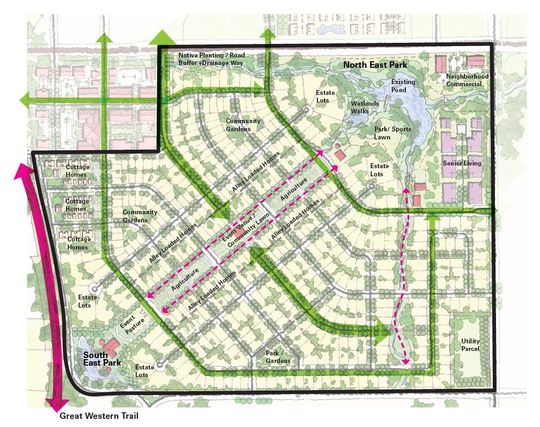

If the Cumming City Council green-lights the roughly $260 million project next month, the Middlebrook development could be Iowa's first "agrihood," a planned community anchored by a working farm or community gardens.

More than 200 agrihoods have popped up across the country, a trend that appeals to consumers who want a slice of country life — big gardens, nature and outdoor recreation — near urban centers.

"The problem with suburban neighborhoods is that to get to anything other than more houses, you have to drive," said Adam Mekies, associate at Design Workshop in Aspen, Colorado, an architectural firm that's designed several agrihoods.

"Instead of pushing agriculture farther and farther from town, how do you bring it back in?" Mekies said.

Bruere, a partner in Iowa-based Diligent Development, believes Cumming is the perfect place for the concept: The town of 400 already is a destination for thousands of bikers who ride eight miles on the Great Western Trail from Des Moines each year.

With rolling hills, ponds and timber, the 700-home development could take Cumming's population to close to 2,200 within a decade.

It's a shift from centering homes around golf courses, said Bruere, who visited his first agrihood in Virginia and was "blown away."

Families feed chickens and goats and learn to plant and pick vegetables and fruit. They buy produce directly from the local farmer through CSAs or at local stands and markets.

"Getting kids outdoors is an important thing these days — getting them off their devices and their hands in the soil," said Daren "Farmer D" Joffe, a California consultant helping Bruere plan the agrihood.

Iowans need only look to the growing popularity of farmers markets to understand why argrihoods resonate with consumers, said Larry James Jr., a real estate attorney at Faegre Baker Daniels in Des Moines.

"There's a reason tens of thousands of people go to the Downtown Farmers Market each week," said James, the chairman of the Urban Land Institute of Iowa. "It's cool. They want a connection with their farmer."

'Nature in our backyard'

Mayor Tom Becker said residents want to keep Cumming's small-town feel, even with development knocking on the front door.

Microsoft is building its largest U.S. data center nearby, and Veterans Parkway, also called the Southwest Connector, is under construction just north of town.

That will make getting anywhere in the metro area even easier than it is now. Cumming sits close to Interstate Highway 35 and Iowa Highway 5. West Des Moines is 10 minutes away, and downtown Des Moines, 20 minutes.

"We don't want to become a big city," Becker said. "We know that from survey after survey."

So far, Becker said, Diligent Development's plan fits with the city's idea of staying close to Iowa's rural roots. "What we see right now, we like," he said.

Bruere, who also is president of the Peoples Co., a Clive farm management and brokerage firm, said his farm team gets calls every day from families wanting a few acres to build a home on.

"People want to buy 2 acres in the country to have some chickens, a dog and horse, and that's tough to find," he said.

Bruere thinks this project can give families the country feel they want without "chopping up a bunch of farms."

The project calls for a mix of residential options: senior housing, apartments, condos, townhomes, homes for first-time buyers and high-end estates.

Homes in one large neighborhood face gardens in a greenway park that's centered by a "celebration barn" and paths that connect to the 17-mile Great Western Trail.

The homes, designed with front porches and alley-garages, sit on tree-lined sidewalks. The development's retail-commercial center would butt up to Cumming's downtown. Now all a farm, Cumming would need to annex the land if the project moves forward.

"We all want that piece of nature in our backyard," Bruere said.

Agrihoods aren't 'an easy thing to do'

While less costly than a golf course, an agrihood can be difficult to pull off, experts say. In 2014, Hubbell Realty considered building a development around a farm or gardens, but eventually decided against it, saying the financials didn't work at the time. The company was concerned homeowners would lose interest in maintaining the gardens and they would "become an eyesore for other homeowners."

The company hasn't reconsidered the concept, focusing its efforts in downtown Des Moines, where it has several large projects. Joffe agreed that agrihoods aren't "an easy thing to do."

"It's not business as usual," he said.

Typically, the developer helps set up the farm, such as providing the land, greenhouses and tractor. Joffe said the farm needs the startup assistance to be self-sustaining, whether as a nonprofit or a private operation.

That investment will make the project "different from the tract community down the road," he said. "It's more of a risk but a higher return because you'll have a really unique project."

Agrihoods have taken off in Georgia, Arizona, Illinois, Washington and Vermont, among other states.

In Iowa, Linn County is backing a $120 million residential project that's centered on conservation and built around a working farm. And Pleasant Hill is contemplating an agrihood project as well. Both are in the planning stages.

It's important, Joffe said, that farming ties the community together, both physically and through programming such as cooking and gardening classes. Many developments offer classes for schools, senior and youth groups and civic organizations.

Joffe believes Bruere, who grew up on a farm and runs an ag business, has the background to make it work.

Bruere has yet to decide how the farm would be structured. But the agrihood's large event venue, orchard and vineyard likely will be privately owned operations.

It can't all be an acre and $400,000 homes

Just north of Middlebrook, Bruere is building a more traditional residential and commercial development called Great Western Crossing, valued around $112 million.

Its 300 homes and townhomes would bring Bruere's total development in Cumming to about 1,000 units if the agrihood project moves forward.

The town's iconic schoolhouse, where former U.S. Sen. Tom Harkin attended, is already getting a face-lift, with a new brick facade and windows.

A craft brewer will locate there, although Bruere hasn't named the company yet.

A new building constructed next door will house the brewing equipment and provide bike storage for families who want quick access to the trail, Bruere said. A hops garden is planned out front.

The new brew pub would join the Iowa Distilling Co. and the Cumming Tap, popular destinations for thirsty bike riders.

Full Court Press opened The Chicken restaurant and bar in nearby Orilla last summer.

The development "sounds like it's going to be a small town, with all the modern trappings ... a modern step into rural life," said Jeff Bruning, a partner in Full Court Press, which owns several metro area restaurants and bars.

Bruning is eager to see the development take off. The added traffic will help his business and others.

Bob Moural, the Tap's co-owner, hopes the development brings a mix of ages, housing and businesses. "It can't all be an acre and $400,000 homes," he said.

Moural believes the town's leaders will ensure the community maintains its character with new development. "I know it's eventually going to grow up, and I won’t be the only kid in town."