Jul 30, 2018

The Young Farmers Behind Puerto Rico’s Food Revolution

Ah, Puerto Rico! Land of rum and iguanas, palm trees and paddleboard yoga. I arrived in San Juan two days ago with every intention of reporting briskly and soberly on the state of food and farming here since Hurricane Maria hit last September.

But even the most sober reporter would be entrapped by this island’s enchantments. Since touching down I have: drunk a cocktail called the Tesla out of a lightbulb at the pert little La Coctelera (where the cocktails are quite performative: The Paper Plane is garnished with a folded airplane); eaten deep-fried fish fritters with mayo-ketchup—the island’s preferred sauce; sat with my feet in the sand reading about Lolita Lebrón, the stylish Puerto Rican nationalist who, in 1954, led an attack in which five U.S. representatives were shot, shouting, “¡Viva Puerto Rico libre!” without once rumpling her French-knotted scarf.

This might all come across as frivolous given recent events, but in San Juan, at least, so much has been rebuilt in seven months that it’s hard to find evidence of Maria’s devastation—but for the occasional inoperative traffic light and the blue pointillist dots of FEMA tarp roofs against the composed pastel city. Of course there is damage one can’t see from bar stools or beaches, and I am en route to meet a 34-year-old named Tara Rodríguez Besosa, cofounder of the Puerto Rico Resilience Fund—an effort to help rebuild the island’s beleaguered farms. Rodríguez Besosa is the force behind an emergent Puerto Rican food revolution, and my plan is to join one of her volunteer brigades tilling topsoil at Huerto Semilla (“seed garden”), an agroecological student-run farm smack in the middle of San Juan, at the University of Puerto Rico’s Río Piedras campus.

When I arrive, the scene is a veritable hive of activity: young farmers, almost all women, bent over hoes, ferrying large bunches of holy basil or laying irrigation tape. Rodríguez Besosa, whose pixie cut and thin limbs give her the appearance of a rangy Peter Pan, stands with a shovel by beds of cilantro, mustard greens, and kale. She is physically striking, making a schools not prisons T-shirt, short black leggings, work boots, and dirt smudges look chic. The effect is partly due to her height—she is five feet ten—and her deep outdoor tan, sparkling eyes, and constant smile. She shovels soil through a sieve, while directing admiring young volunteers and answering her constantly ringing phone: Here’s where to deliver lunch; this is what time the car should meet her in New Orleans in two days; here’s where to send the next brigade.

Restoring Puerto Rican agriculture is a complex and novel project, since the island mostly stopped producing its own food long ago. By a conservative estimate, Puerto Rico imported at least 80 percent of what it consumed before the hurricane. The story of why in the briefest possible terms: Farming declined during Puerto Rico’s days as a Spanish colony, when native agriculture ceded to large colonial plantations. Under U.S. administration, beginning after the 1898 Spanish-American War, Puerto Rico was subjected to a combination of economic restructuring, industrialization, and the growing stigma of being perceived as a rural, peasant island. Surviving farms grew profitable sugarcane, coffee, or, in rarer cases, plantains and other fruits. By the turn of the twenty-first century it was all but impossible to procure anything locally but a very limited set of crops.

This does not perhaps sound so bad—until you consider the high environmental costs of transporting the island’s food. And the poignant lesson of Maria, which destroyed 80 percent of Puerto Rico’s crops in addition to roads, homes, vehicles: that dependence on imports left Puerto Ricans uniquely susceptible, in the face of a natural disaster, to starvation.

“They say that during Maria, Puerto Rico only had enough food for one week,” says Carmen Yulín Cruz, the mayor of San Juan, who rose to international prominence feuding with President Trump over aid. “I hate to say anything positive about Maria. But what the hurricane did was force us to look at the realities of life here and how our dependency on the outside weakens our ability to ensure our people are taken care of. Maria made it evident that we need agricultural sovereignty.”

Sylvia De Marco, a collaborator of Rodríguez Besosa’s and co-owner of a San Juan boutique hotel called the Dreamcatcher—in whose Goddess Suite I’m spending the week—agrees. “After the hurricane, even people who didn’t care about food started to care. It really opened people’s eyes: that we have to depend on our soil, not shipping containers.”

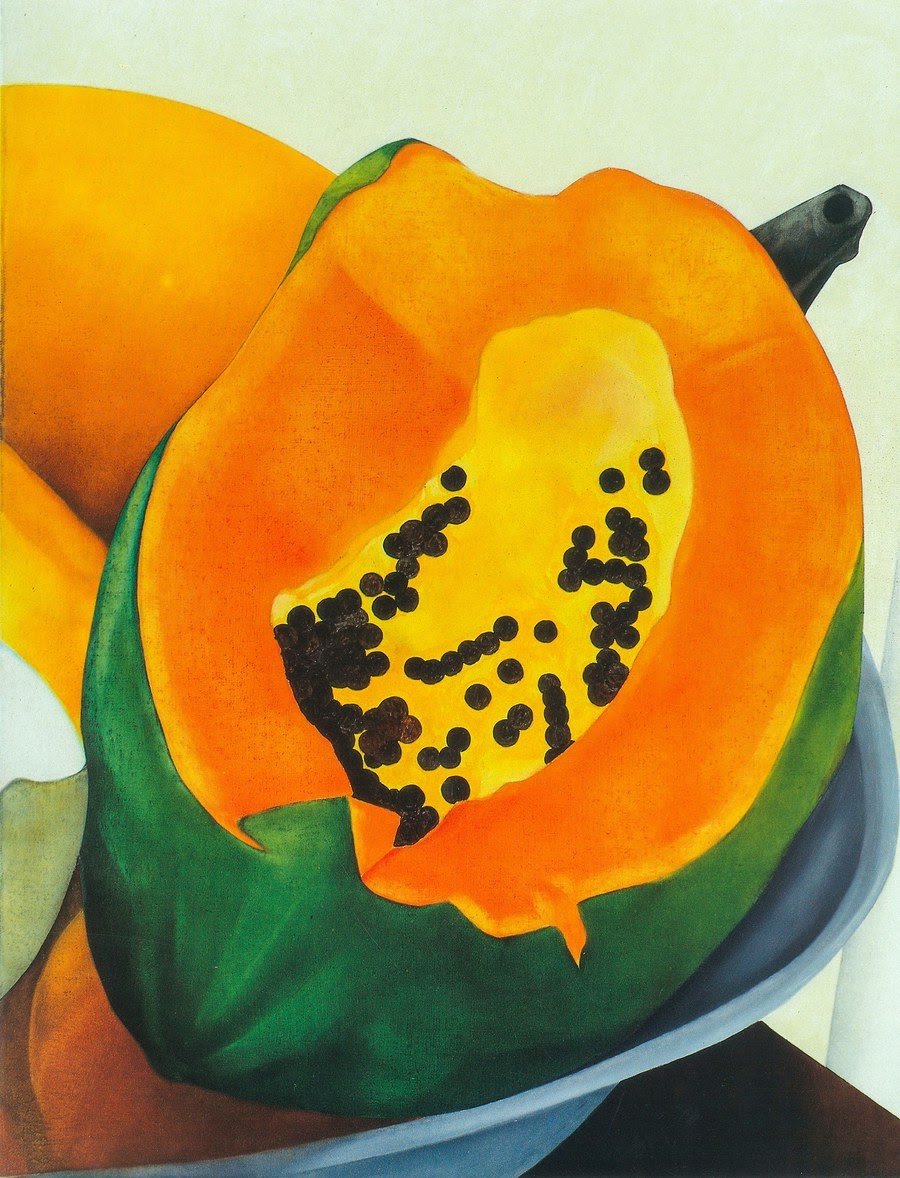

Puerto Rican farming was highly limited before the hurricane. Recovery efforts envision a more diverse crop. Detail of Papaya, by Ana Mercedes Hoyos. (Photo: Courtesy of Ana Mercedes Hoyos. Papaya, 1994. Oil on canvas, 23.6ˮ x 23.6ˮ)

Enter Rodríguez Besosa, an artist turned farmer who studied architecture at New York’s Pratt Institute and helped run a gallery in Red Hook, Brooklyn. A decade ago, missing home, she moved back to Puerto Rico. She helped out on her mother’s tiny organic farm to make money while she opened a cultishly popular, illegal, and not at all lucrative bar in San Juan. She quickly detected a problem. “There was one farmers’ market every two weeks, and you had to be up at 9:00 a.m. to get anything. I was running a bar. I wasn’t waking up at nine.” Some small vegetable and meat farms, like her mother’s, existed around the island, but farmers and consumers had few ways of getting together.

Rodríguez Besosa, a natural entrepreneur, decided to fix the problem. She accepted $10,000 in seed money from a friend, rented a warehouse, named it El Departamento de la Comida (“the department of food”) and started driving around selling boxes of local vegetables. “The vegetables I bought had to be not just local but sustainable—agroecological, biodynamic,” she says. Her quick conversion to the dogma of sustainability may be genetic. Her mother was a model and fashion retailer turned farmer; her sister studied biology before taking over the family farm in 2011. “My point was we could not afford to go on farming unsustainably in Puerto Rico,” she says.

The response was enthusiastic. María Grubb, a Puerto Rican who spent about seven years cooking at New York’s Pastis, the Modern, and Maialino before returning to open Gallo Negro in San Juan’s bohemian Santurce neighborhood, says that when her restaurant opened, El Departamento de la Comida was the only place she could find fresh local vegetables. Juan José Cuevas, former chef at Blue Hill in New York City, who moved here in 2012 to take over the kitchen at the Condado Vanderbilt Hotel, agrees: “Tara was doing this when no one was.”

“We detonated something really interesting,” Rodríguez Besosa tells me over a delightful lunch at Huerto Semilla of rice and beans, roasted eggplant, and local lettuces with orange vinaigrette. “We were all over the newspapers. The whole thing erupted. I was like, I have no idea what this is, but, holy shit, it is amazing.”

Her next step was to transform El Departamento de la Comida into a restaurant. She bought an $80 stove, installed it in the warehouse, and let friends and visitors make simple dishes like pumpkin soup and pesto. “We had two to three people in the kitchen. Maybe it was an artist who cooked outside, or maybe it was someone who liked to cook, like Paxx Caraballo Moll”—a Puerto Rican chef getting accolades for the new restaurant–in–a–tiki bar Jungle Bao Bao. Furnished with folding tables and chairs, serving a changing vegetarian menu of whatever local farms harvested, the restaurant quickly became beloved, akin to Brooklyn’s Roberta’s—shabby, a little uncomfortable, delicious.

“Then the hurricane hits us, and bang, we’re gone,” Rodríguez Besosa says. The restaurant flooded, then was repeatedly looted. Stranded in New York for an event while the storm raged, Rodríguez Besosa gathered friends to create her Resilience Fund and pitched in with the ad-hoc Queer Kitchen Brigade, which canned food to send to the island. Rodríguez Besosa brought some of the cans and jars back herself, along with seeds and farming tools—by joining a delegation aboard a Greenpeace ship.

Since November, Rodríguez Besosa has sent farming brigades, in her brightly painted Guagua Solidaria (“solidarity van”), to more than 30 gardens and farms all over the island, distributing seeds, building rainwater collection systems, donating tools, cooking meals, giving acupuncture treatments, and providing general spiritual uplift. She plans to help 200 farms before the campaign ends. “And if you’re growing food in your backyard, you’re included,” she tells me. “If you sell at farmers’ markets, you’re included. If we want to create autonomy in Puerto Rico, it will have to be in different ways. We have to do urban agriculture; we have to do school farms, community farms, backyard gardens.”

Mayor Yulín tells me that Rodríguez Besosa’s role in the island’s future is unique. “Tara is giving agriculture a new face,” she says. “She’s found a way to convey the importance of a new local agriculture at a primal level, with the technology and vision to ensure it’s done in a socially responsible and fair and ethical way. She’s taking something old and making it exciting.”

Rodríguez Besosa isn’t alone; others on the island have rallied to support local agriculture too. The Dreamcatcher’s De Marco offered guests the opportunity to volunteer at a farm called Estancia Verde Luz in nearby Ciales last spring. She tells me, “Our menu is all local, and Estancia Verde Luz was the main farm who sold to us. It was completely trashed in the hurricane. So we had guests help with cleanup. People felt really good to be supporting the economy, and at the same time helping a farm rebuild.” In May, De Marco launched a monthly dinner series called Nuestra Mesa (“our table”) in collaboration with Rodríguez Besosa: four courses of local vegetables, served in the Dreamcatcher’s airy kitchen and patio, attended by hotel guests, locals, and farmers.

An hour and a half east of San Juan, I pay a visit to an Ayurvedic biodynamic farm named Finca Pajuil that Rodríguez Besosa has told me is a model of resilience, replete with rotation planting, rainwater collection, aquaponics—the kinds of things Mayor Yulín says must be part of Puerto Rico’s agriculture.

An unfortunate misunderstanding with my phone’s GPS system leads me to a distinctly un-Ayurvedic pizzeria (I recommend the calzones), but eventually I arrive at my destination, and the bright-eyed head farmer, Jey Ma Tulasi, greets me at the gate—an inexplicable but not entirely unattractive green botanical V painted down the middle of her face. Tulasi shows me where neem and breadfruit trees once divided her land from the road, their disappearance depriving her crops of shade. Still, it’s impossible not to see how many more birds flock to Tulasi’s moringa and banana groves than to neighbors’ backyards, how many more bees buzz in flowers, and how healthy her curving spirals of holy basil and tarragon, aloe and mint make the land. Her little shop sells a homegrown, Ayurvedic version of adobo made with her own turmeric and local sea salt. There is moringa for sale by the bunch, and curry leaves. I’m struck by the hopefulness of the hugelkultur beds—deep garden plots made from fallen trees—which are already thick with pumpkins and sweet potatoes.

Over a final dinner with Rodríguez Besosa at Cuevas’s 1919, inside the Vanderbilt, I note that women seem to be leading this movement. “In terms of activists inside the farming movement, at least half of them are women,” Rodríguez Besosa says. “And more than half the farmers I work with are.”

What follows is one of the more exciting meals of my recent memory: white gazpacho; lobster with eggplant and mozzarella; tuna tartare with caviar; barely cooked tuna with tomatoes; salmon with fresh shelling beans; local goat-cheese ravioli; and a local fish from the snapper family called cartucho—much of which comes from farms and fishermen on the island, whom Cuevas buys from directly.

Cuevas joins us as we share coconut sorbet and a salted caramel–and–chocolate tart. He sees another silver lining in Maria. “Obviously, six months ago things were very bad,” he says. “But six months have given people time to stop, think, and grow things. The Puerto Rican diet of rice, beans, plantains, and root vegetables is very earthy, but it also takes a really long time to grow.” The destruction of plantain groves has encouraged the planting of fast-growing beets, greens, tomatoes instead—ingredients healthy diets demand.

We end the night tasting three homemade jams from a woman who delivers them biweekly: one pineapple-and-mango, one papaya, one guava-coconut. They are faultless. I wonder whether I could find them in New York.

Rodríguez Besosa’s sparkling eyes light up further. Her next project is starting her own farm on land she bought last week. “It’s in a small community in Caguas, 45 minutes south of San Juan,” she tells me, so excited she’s nearly vibrating. “I’ll finally produce my own food on a larger scale.” It’s also the next iteration of El Departamento de la Comida.

“This will be a model farm that hosts only workshops using permaculture and agroecology frameworks, and a collective for queer and trans people who want to work the land.” She plans to build a commercial kitchen on-site and use primarily the harvest from the farm itself. Next up, she says, as we chase our jam with petits fours: “our own product line.”

by TAMAR ALDER